Dunbar's Number & Community Size

What’s the ideal size of a coliving community?

What’s the ideal size of a coliving community?

Robin Dunbar was an anthropologist interested in a similar question - not for coliving communities (he hadn’t yet discovered Supernuclear…) - but for organizations.

Dunbar was trying to estimate the largest group size that one can maintain stable social relationships. Or as Dunbar put it: “the number of people you would not feel embarrassed about joining uninvited for a drink if you happened to bump into them in a bar”

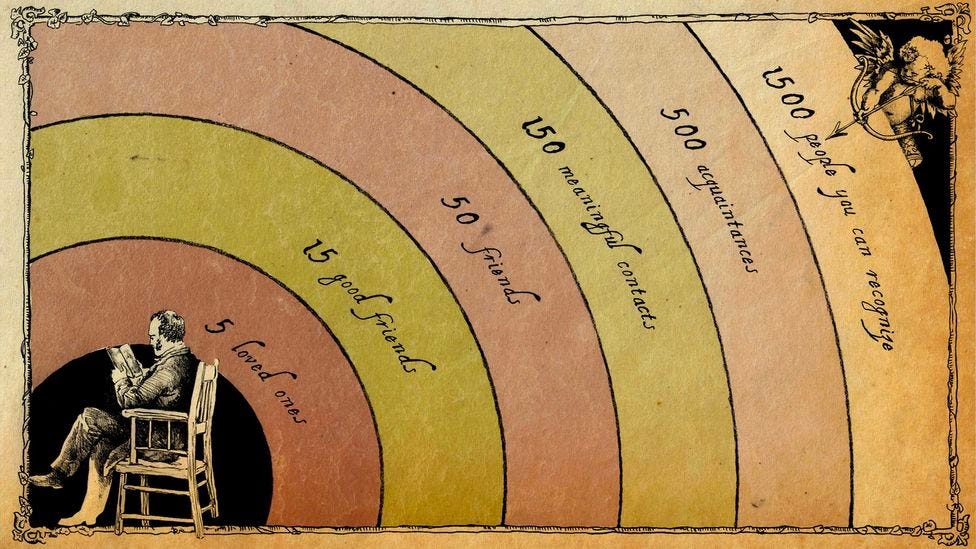

So he went to study different kinds of primates and what sized groups they naturally formed as a function of their brain size. He extrapolated to the human brain and … boom. He came out with a number – 150 people, aka “Dunbar’s Number.”

Dunbar claims you can only have stable social relationships with a maximum of 150 people. There is plenty of critique of his methodology, but various organizations like GoreTex and the Swedish Tax Authority have taken this to heart by splitting their divisions at 150 people.

–

In the spirit of methodologically-suspect social science, I want to hypothesize various “Dunbar’s Numbers” for coliving community size. And give some finger-in-the-air intuition of why I think this might be the case.

2-7 people coliving: “Roommates”

Definition: Intention not required.

“Roommates” is the first scale level of living with friends. And if you have great roommates, this can be wonderful. But it’s not what we study here at Supernuclear.

Roommates don’t need principles. They don’t need values. They don’t need much in the way of systems or intention. They can just live together informally and if everyone is respectful and likes each other it will just sort of work out.

In my mind, a living arrangement makes the leap from roommates —> community when you break this threshold and you start needing values, processes, and identity to organize people effectively.

That’s when things get interesting. And that’s what size real community starts at for me …

8-12 people coliving: A “Squad”

Definition: Where everyone is close to everyone (and knows everyone’s relationship to everyone).

Suppose you have 8 people in a community. That means you personally have seven 1:1 relationships within the group. Humans are good at maintaining a lot of 1:1 relationships. We can easily understand how we relate to 7 other people.

But suppose I want to also understand how Bob and Alice relate to each other. You might be asking a question like “would Bob and Alice be good co-leads for recruiting?” or “which two people wouldn’t mind sharing the bathroom on the second floor?”

To understand questions like this, you not only need to understand your relationship to Bob and Alice. You need to understand everyone’s 1:1 dynamic with everyone else. This is a lot more to get your head around.

High school math flashback: How many total 1:1 relationships are there in an 8-person community?

The answer is 28 .. or more generally for n people, n*(n-1)/2. Here’s the mathy explanation for that.

To understand everyone’s relationship to everyone else, you need to understand 28 different interpersonal dynamics.

My definition of a squad: A group that understands every 1:1 dynamic in the group.

And because this scales as N^2, that number rises rather quickly as the community grows. Add just 4 more people (12 total), and suddenly you have 38 additional 1:1 interpersonal dynamics to understand (66 total).

Based on what I’ve seen, people start to struggle to do this above 12 people (66 relationships). It’s not that the community gets bad, it’s just different. It’s no longer a squad. There’s too many interpersonal dynamics to understand.

At a 8-12 person scale, you can:...

Have a single-threaded conversation over dinner.

Get everyone together for a weekend retreat.

Get everyone to vote reliably on a Slack poll.

So once you are above ~12 (remember: fuzzy math here), you are something else. You are an extended community…

13-25 people: A “Congregation”

Definition: Close 1:1 relationships, but inability to understand or gather the whole

At this size, we can no longer understand everyone’s relationship to everyone. But we can still have meaningful 1:1 relationships with all the people.

I may not understand Bob’s relationship to Sally, but I am close with both Bob and Sally.

It’s hard to get everyone together for a meeting reliably, but we can still solicit and consider everyone’s input through other means.

Not everyone was present for a decision, but everyone still knows what’s going on in the community. A congregation can stay in sync without too much effort, but has trouble getting all voices in the room at the same time.

High-growth startups look back and talk about how the culture changed around 25 people. Everyone broadly knows what’s going on. You don’t need formal internal comms. People just talked and found out about things. There’s natural coherency and synchronicity.

After about 25 people this changes and you’ve become something else…

25-150 people: A “Constellation”

Definition: Stable 1:1 relationships, shared values, but splintering of the group.

Above 25 people, hierarchies appear. You need formal communication structures to keep everyone on the same page . More structures, more systems.

You can still know everyone personally. You might not be close to them, but as Dunbar observed you can still have some kind of stable social relationship with them.

You can share intention, you can share values, you can all participate in processes. When there’s issues, you can work it out with each other 1:1

But pockets will form independent of the whole. It’s no longer just one monolithic thing. It will branch and diverge and surprise. You might start to hear the word “they” instead of “we.” Instead of thinking about individuals, you may start grouping people together and saying things like “the new people” or “the morning workout crew".”

150+ people: Probably no longer a community (perhaps an ecosystem?)

Above 150 people, our neocortexes start to give up. We can no longer have stable relationships with all the individuals. Instead, we have some sort of relationship to the idea or concept.

Bob from the legal department is no longer Bob, a real person. Now he’s just “the guy from legal.” But both Bob and I work for an organization that has some shared meaning to us. The idea binds us more than the our individual relationship.

At this scale, it probably ceases to become a community with a reliably dense net of 1:1 relationships and stable boundaries.

This is an ecosystem. A network of coliving communities might be in this category. It’s a very different beast than the coliving communities we profile in this publication.

So, what’s the best number?

There’s no best number.

That being said for most communities, 8-12 is a pretty safe number for good dynamics. Below that and things might feel a little barren (6 people in a city might mean that 2 of them are home on a given night). Above that, and you are dealing with a proper complex organization.

A lot of the successful communities we profile in Supernuclear fall into this range. And I think that’s no coincidence.

Radish recently expanded above that threshold (now 18 people, including the infants), and we’ve already noticed it’s different. Not worse, just different. A lot of our informal processes are not quite working like they used to, and we are having to replace them with something more structured.

On the plus: A lot MORE is going on. The place is more vibrant. Not everyone needs to be involved with everything all the time.

Pros and cons.

As you build your community, mind the neocortex and its limitations.

Curious about coliving? Find more case studies, how tos, and reflections at Supernuclear: a guide to coliving. Sign up to be notified as future articles are published here:

And you can find the directory of the articles we’ve written here.

I really like your publications, I find them very useful, relatable and easy to read. Such a pleasure. Thanks a lot for you work 🙌🙌🙌

I recently started learning about pocket neighborhoods which purposefully try and build clusters of houses around a small shared greenspace. The max number of houses seems to be 18.