How to co-buy a vacation home with friends Part 2 - Legal and financial structures

The meat of it.

[The fine print] I am not a lawyer. This is not legal advice. You should hire your own lawyer. This is meant as a resource to help you in thinking through some of the issues.

Welcome to Part 2 of the Story of Duck Cloud - a vacation home co-bought by friends. You can find Part 1 here.

This episode of the meat of it. It’s long, it’s detailed. And I hope it will help you one day own a vacation home with your friends.

We’ll talk about legal and financial structuring for a joint vacation home. We’ll also provide our actual legal docs, which I hope will save you thousands of dollars and lots of time.

Preface: What to optimize for (and what will get in the way)

My #1 piece of advice: Most of your agreement should fit on the single side of a notecard.

If it doesn’t fit on a notecard, your agreement is too complicated.

There may be some fine print and edge cases that don’t fit, but someone joining your property should be able to understand 90% of what’s going on by reading that notecard.

Here is our agreement on the back of a notecard (we’ll come back to each of these points in a bit):

Two things will stand in the way of you making a simple, clean agreement: Fairness and lawyers. You must work to counteract both of these.

Fairness gets in the way of simplicity

Fairness is good. It is often in opposition to simplicity.

Example: You could try to track the number of days everyone spends at the property and divide up the costs of toilet paper based on the number of days. This would be more fair. It would be significantly more complicated.

Alternatively, you could say a) over time this sort of thing will net out ... I might use more TP, but someone else takes longer showers b) even if Person A ends up getting a “better deal” than person B, this is still a great deal for both of them.

IMO (and with 3 communities of experience): Trying to make everything perfectly fair is more likely to lead to conflict and unhappiness than making things simple and intentionally a little unfair.

Simplicity is critical because a group of people is not going to remember all the rules you set out. Rules that people don’t understand or remember are rules that won’t be followed and will create conflict later.

Flexibility is critical because however you think things are going to work, something is going to change. If you are trying to precision-engineer a “fair” agreement upfront, you will soon end up with an unfair agreement once things inevitably change and people will be upset. If it was never fair to begin with, people won’t fixate on fairness.

Lawyers get in the way of simplicity

Lawyers become lawyers for a reason. They love detail. They see risks all around. They think of things through the lens of companies (where complexity is fine) rather than groups of friends (where simplicity is preferred).

I will talk more about how to work with a lawyer below. But don’t let your lawyer overcomplicate your agreement. Ask them over and over “is there a simpler way to do this?”

Unpacking the Duck Cloud agreement

Let’s talk about each of these points, why we chose them, and what the alternatives might be.

I am not suggesting all co-owned vacation homes should operate this way. You may have good reasons for doing things differently. But this is what we landed on for us.

Point #1: No person can own more than 30% of the LLC.

A core decision you need to make: Who is in charge?

For us, we said no single person is in charge. How we enforced this in practice is writing a clause into our LLC agreement saying that no one person is allowed to own more than 30% of the LLC shares.

Here is our distribution of shareholding at time of purchase:

What this means is that any decision (usually 50% vote of shares … more on this later) requires at least 3 people to agree.

Having no one person in charge comes with a long list of pros and cons. And you might very reasonably choose differently. The disadvantage to this structure is that no one person feels personally responsible for the success of the property. Who’s going to be the one who pushes to fix the roof, for example? The advantage is that everyone feels at least some meaningful sense of ownership.

—

Alternative to consider: Benevolent dictator owns >50%

Why you might choose this: Someone has more capital than everyone else. Or you want the simplicity of one person making decisions.

You could also put restraints on the benevolent dictator: e.g. the benevolent dictator can not make X decisions without majority approval from everyone else.

Why we didn’t choose this: No one wanted to be the benevolent dictator.

—

Point #2: Everyone gets to use the property as much as they want, but no one should live there permanently.

Deciding who gets to use the property and when is a complicated can of worms. And it’s really hard to lay out a permanent policy upfront. You just don’t know what the future holds or how the property will get used in practice before you own it.

This is a 10-year journey and we realized that defining all the specifics here wouldn’t be helpful. Instead we wrote down an overarching principle and came up with a process for modifying the specifics as we learned more and the situation evolved.

Our guiding principle: “Everyone gets to use the property as much as they want, but no one should live there permanently.”

Deciding on specifics: We will ratify a more detailed usage agreement once a year by majority vote.

The guiding principle makes it so we are aligned on the big picture.

The fluid usage agreement allows the specifics to change over time.

Each year we might decide to do things slightly differently: Maybe we allow guests one year, but not the next year. Maybe we decide to sell temporary access to a person who is not an owner. We can treat this as yearly experiments rather than codified law.

But mostly, usage is governed by fluid norms rather than any written agreement. The nice thing about doing this with a trusting group of friends is that people tend to behave in a considerate, accommodating way. If your friend wants to host their engagement party there, it probably doesn’t need to be codified in the official rules. People will just allow this to happen. If you don’t trust people to act in this way, then don’t include them in your project. No written agreement is going to save a lack of trust and mutual respect.

—

Alternative to consider #1: Some people live permanently on property, others use it as a vacation home

Why you might choose this: Rural properties are hard. Having a permanent caretaker on property is helpful.

Why we didn’t choose this: We didn’t have a ton of bedrooms at the place and didn’t want to give over 1-2 permanently to someone.

—

Alternative #2: Timeshare - everyone gets X weeks

Why you might choose this: If you are really concerned about overuse you might want to limit people’s time.

Why we didn’t choose this: The point of owning a place with friends is to see them. We didn’t want to put limits. We wanted this to feel like a home that we can show up to anytime.

—

Point #3: We will split the operating costs equally irrespective of shareholding or usage

This was an important principle for us. It simplified a lot of the agreement.

Our property costs roughly $100k per year to run. This includes property tax, insurance, utilities, supplies (think: paper towels, lightbulbs, olive oil), mortgage interest, firewood, repairs, maintenance reserve.

We did the simple thing: Split it equally by the number of investors.

Will some people use the property more than others? Of course.

Does everyone get access to an amazing property whenever they want at a fraction of the cost and effort of owning it themselves? Most definitely.

It is simple, not fair.

A couple details here worth mentioning:

Functionally: We do a yearly “capital call” where members pre-pay the operating costs for the upcoming year into the LLC bank account. This is a formal legal obligation. The LLC is legally allowed to demand these operating costs from each of its members and the members are legally obligated to pony up. It’s serious stuff!

What about couples vs singles? We invented the notion of a “usage point.” We said each couple counts as “1 usage point” and each single also count as “1 usage point.” A usage point corresponds to a bed. When we divide the costs, we divide by usage points, not by people. So couples end up paying half of a single per person. We are generous with +1s with singles to compensate for this.

Opting out: We also have a provision that allows members to opt out of operating costs with 1 years notice. If they opt out, they are not allowed to use the property anymore. We put this escape hatch in in case someone moves across the world for 2 years, for example. They can reactivate their membership later when they return and will begin paying operating costs again.

We consider the mortgage interest (but not the principal) to be an operating cost of the property and it is split equally between members regardless of shareholding.

—

Alternative to consider #1: You could try to add up the number of days people spend on the property

Why you might do this: If you expect usage to be highly unequal and unpredictable

Why we didn’t do this: Doesn’t allow us to collect operating budget upfront from members. Violates the simplicity > fairness rule.

Alternative #2: You could assign different numbers of “usage points” to each member if you expect people to use it more. E.g. Heavy users pay 2 shares of expenses rather than 1.

Why we didn’t do this: Complicated and unnecessary.

—

Point #4: One share = one vote. Most decisions are majority vote, some have a higher bar. New members require a consensus vote.

This point lays out what decisions we make and what the voting threshold is for making them.

We do votes, we do them fairly infrequently, and only for big ticket items.

We wouldn’t do a formal vote on something like “should we be vegetarian” or “can Alice host an event on Wednesday.” Our legal docs solely focus on major property and financial decisions. Other decisions are made informally, fluidly, and with a do-ocratic spirit.

Since most of the big stuff pertains to the property itself, we thought it was best for people's “vote” to be proportional to their ownership stake, i.e. the number of shares they have in the LLC. This means that people who put in more money have a larger say in these decisions.

A couple things to highlight here:

We allow people to spend up to $2k without any formal approval. This allows someone to call a plumber to fix a leaking toilet without calling a formal vote of shareholders. It’s a show of trust, and we trust everyone to spend money wisely. In practice, we have a norm that people give a heads up for a purchase (“hey, I’m going to buy this $100 blender, any objections?”) but that’s not a legal requirement.

We consider adding new members to be the most important decisions we make as a group. It’s the only thing that’s 100% consensus. We never want someone to feel uncomfortable with a new member.

There is a “Manager” of the LLC who is the formal executive. This role is mostly administrative. They are the person who formally does the LLC things, like sign documents, file taxes, etc. We vote on this person and rotate the role.

We have a 90% threshold for changing our agreement. The spirit of this is “mostly consensus, but we won’t let one holdout person gunk things up.”

Note: This set of decision thresholds is fairly similar to how a vanilla real estate LLC (like the one that might own the apartment building in your city) does things. It’s well-trodden.

Point #5: There is no exit on-demand. If you want to sell your shares, you must find a buyer and the LLC must approve that buyer. There is no timetable for selling the property.

This is another simplifying decision.

There is no guaranteed exit. There is no timetable. Your investment in this property is locked up until we vote as a group to sell.

This one has big trade-offs. But we felt it was the right decision.

First, it’s worth considering what you’d have to do as an alternative. If you wanted to give people a way to remove their investment, two very tricky things would need to happen:

All the other investors would need to put up extra money to buy them out on-demand

You’d have to have a formula for deciding on a fair price

For the first, we didn’t feel like it was fair to expose the other members to an unknown liability of forced buyouts.

For the second, the LLC would have to have a mechanism for pricing people’s shares. How do you do that? There’s no easy way! Appraisals of large rural properties are scattershot and inaccurate. Any mechanism for getting to a “fair price” is hard, expensive, likely inaccurate, and prone to conflict. We chose not to invite this world of pain.

So we don’t address requested buyouts at all in our agreement. Someone can sell to another shareholder and they can work out the price of shares between them. But it’s not something the LLC gets involved with at all.

But what if someone runs into financial difficulties and needs to be bought out (and can’t find a buyer)? We keep this in the social rather than legal realm. As friends, we take care of each other. We’d try to help them out. But we don’t try to codify this requirement in our legal agreements.

The trade-off to not allowing on-demand buyouts is that people are making a big commitment and have their money locked up for a while. But remember, it’s a whole lot less money than owning a home on your own.

We felt this was a trade-off worth accepting for simplicity, stability, and reduced chances of drama/lawsuits/etc.

—

Alternative to consider #1 - Allow buyouts over X years. For example, give 3 years for a buyout to happen or spread out the buyout

Why you might choose this: You want people to be able to exit, but not have a sudden shock to the LLC members.

Why we didn’t choose this: All the reasons stated above.

Alternative #2 - Agree to sell the property in X years.

Why you might choose this: Everyone knows how and when they can get their investment back.

Why we didn’t choose this: We want to hold it for an undetermined amount of time.

—

Point #6: Pete is the guarantor of the loan. If the LLC misses a loan payment, Pete takes over control of the property.

Someone had to guarantee the loan. Pete (not his real name) decided to generously do this. He is taking on the risk of this being a disaster.

In exchange, we put in a protection for Pete: If the LLC misses a loan payment (or is going to miss a loan payment), Pete takes over the property. This means that he now makes all the decisions (no one votes anymore) and that no one else is allowed to use the property unless Pete says.

In practice, Pete would have a few options here. He could sell the property. He could rent it out to cover the expenses. He could renegotiate terms with the rest of us. But we’ve essentially given up our rights by not holding up our end of the bargain and keeping the property afloat.

Everyone still owns their shares of the LLC (and would get their share of a sale) but we lose control of how the property is used and governed.

Entity type: LLCs vs other options

Notice, I didn’t start with entity type. First figure out what you want to do, then pick the entity type that suits.

I don’t think entity type matters very much, and people make way too big of a deal out of this.

You can be a LLC, you can be a co-op, you can be a TIC, you can be a non-profit. What matters most is what’s written in your agreement, not how the IRS categorizes you.

You can be an egalitarian LLC. You can be a despotic non-profit. Entities are just containers, they don’t determine your fate.

We chose an LLC. Why? It’s easy, flexible, everyone knows how to deal with it (banks, insurance companies, lawyers, municipalities). And within an LLC framework, we can basically govern ourselves however we want.

I think you need a really good reason to not structure things as an LLC. You are making your life more complicated by choosing any other structure. And whatever you think the benefit is: You need to ask yourself “could I accomplish this same thing simply with an LLC?” I suspect in most cases, the answer is yes.

There may be different tax treatments and you should talk to a CPA about this. Two things to ask about are whether the mortgage interest deduction and the $250k capital gains exclusion apply.

If you think I’m not appreciating something here, feel free to comment below with another viewpoint.

Legal docs and working with lawyers

Imagine you are creating a personal website. You might hire a designer to help you make your website look great.

You probably wouldn’t expect your designer to know what content to put on the page. You’d have to give them the content as a starting point.

Working with a lawyer is similar. You want to spell out your vision for your agreements in as much detail as possible.

The lawyer’s job is to turn it into an official legal doc and help you think through risks and edge cases.

You come up with the content of your agreement. Not your lawyer.

There are two reasons this is important: 1) You know your vision, your lawyer doesn’t 2) Lawyers are super expensive. Ours was $600 per hour (!).

We sent our lawyer a detailed plain-english brief and said “make this into a legal doc.”

In the course of creating the legal doc, the lawyer raised a bunch of points we hadn’t considered. We made some revisions to our terms based on their feedback. There were 3 drafts and then a final version. In total, it was 5 hours of the lawyer's time. That was $3k. Then there was another $1k of expenses related to the SEC filings we needed to do.

How to pick a lawyer

Figuring out how to find a lawyer is tough. I’ve struggled with this. If you are a lawyer who specializes in this kind of stuff, please get in touch!

The phrase you probably want to use for the search is “lawyer who does real estate partnerships and LLCs.” They may have never done a communally owned property, but that’s okay. 90% of what is in your agreement is going to be generic “there’s a property with a bunch of investors” stuff. And this is a well-trodden path. Any lawyer worth their salt will already have a template they use for this sort of thing.

You want someone who is in your state. There's a lot of state-specific nuance.

And you’ll want to get a solid estimate on hours based on your brief. Send your term sheet and make them give you an estimate. Here was our original brief as an example.

And critically: Only 1-2 people should interact with the lawyer. Getting a group on the phone with a lawyer is a disaster and will rack up huge fees. Be efficient, clear, and do the work aligning your group beforehand.

The loan

Everything we wrote here about getting a loan still applies.

A few points of emphasis:

Banks will have different underwriting standards for a rural home owned by an LLC (or another type of entity) then an individual buying their own home in a city. Don’t assume an easy process or the best possible terms (e.g. you may need to put down a 40-50% downpayment). And talk to a lot of lenders and do it early.

Someone (or multiple people) are going to need to guarantee the loan personally. Banks won’t usually lend to a naked LLC that you just created without a guarantor. You can decide whether to compensate the guarantor. In our case, we had one guarantor who generously did it without compensation. Our “Point #6” above protects the guarantor.

Mortgage payments are divided into mortgage interest and mortgage principal. We deemed the mortgage interest as an operating expense which gets split equally by the members. The mortgage principal, however, is treated differently in our structure. It is paid in proportion to shareholding, so people’s shareholding %’s don’t change as we make mortgage payments. We do a yearly capital call to the investors for the mortgage principal payments for the year ahead.

Budgeting for renovations and improvements

Most likely, you’ll want to do stuff on the property after you buy it and you’ll need money to do so.

The easiest time to raise that money is before you buy the property. The hardest time is in the moment you need it.

We raised an extra renovation budget at the time of purchase. The property cost $X but we raised $X + 10% from the members.

In addition to this one-time pre-raise, we have a few additional ways to get money for renovations or improvements.

We invite new members over time. Their investment can be used as new capital for improvements

We accumulate an improvement fund by adding an improvement line item in our operating budget

Legal documents

As promised, here are some template legal agreements. I suggest you send these to your lawyer as a starting point. These are not meant to be used without editing.

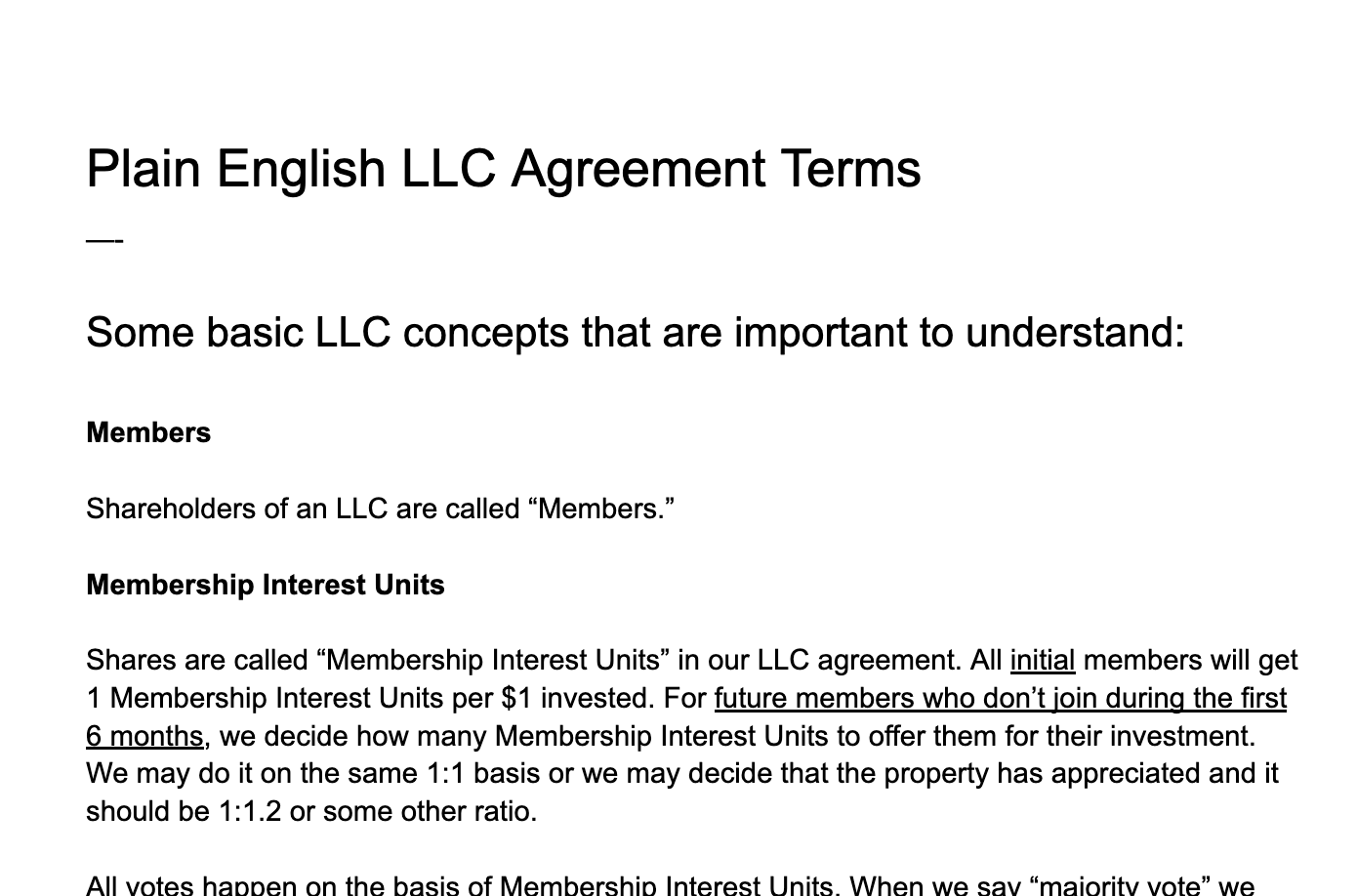

Document 1: A plain-English description of our legal terms and processes for members

Document 2: The LLC Operating Agreement that governs the LLC. It is the big one. It’s long, intimidating but most of it is standard boilerplate legal text for LLCs owning property.

You may also need your lawyer to prepare the following (very common, boilerplate) agreements:

A “subscription agreement” that allows a new or existing members to buy shares from the LLC

A “third party unit purchase agreement” that allows a member to sell their shares to someone else

A “redemption agreement” that allows the LLC to buy

In addition, you want to ask your lawyer about any SEC filings that may be required for people to purchase shares in the LLC. You will likely have to file for an exemption from registering with the SEC. This sounds scary, but it’s will be straightforward for your lawyer to handle.

Conclusion

Whew okay.

This post, particularly the scary docs at the end might feel intimidating. But I assure you, this is all very manageable even for folks without any legal, real estate, or finance experience.

As long as you can write that notecard and have a decent lawyer, this should all fall into place.

And if you are lawyer who works on these sorts of things, please reach out. We can refer folks to you.

These posts are so generous. They make the world a better place. Particularly love the thoughts about how sticking to 100% fairness isn’t a useful practice in creating community. I’d never thought of this and found the concept liberating

Hello Phil,

This is tremendous writing. It is focused on getting the big picture right before diving into details. I can’t believe there are not more comments. My interest is not in communal living, but in buying a ski area cabin with one or two other couples. We might occasionally vacation with the couple(s) as friends, but the primary motive to partner is economic. No one can afford the cabin on their own. Each couple likely using it a few weeks of the year and then renting it the rest of the year hopefully making a modest financial return. Likely hold for 10 years or so then sell as we are in our upper 60’s. Some of your great advice applies but of course it is slanted to communal living. Do you know of another blogger that is more specifically focused on the type of situation I describe?

Thank you again for your writing. It is tremendous.