On Coliving and Tiny Apartments

A cross post from Thesis Driven

Editor’s note: this is a cross post from Brad Hargreaves, founder of Thesis Driven, our favorite blog on real estate.

In addition to deep dives like the one below, Thesis Driven offers useful courses online & in person for real estate professionals and people considering becoming real estate professionals (Gillian recently took one, full review coming soon!). We think our readers would enjoy and benefit most from their upcoming Fundamentals of Real Estate Development course launching on Oct 20. If you’d like to enroll, mention Supernuclear for a 20% off discount.

This post dives into the pros & cons of coliving from the perspective of real estate developers (an ‘incomprehensible’ ‘freak of nature’), which helps explain why relatively little coliving-optimized housing gets built, and why there might be a case for more.

It’s no longer controversial to believe we need more housing, including more diverse types of housing. This is particularly true for “naturally affordable” units that lower the barrier of entry to the most expensive cities and give young professionals a decent place to live without pairing up with roommates and outcompeting a family for a multi-bedroom unit.

But there’s less clarity on what, exactly, needs to be built.

The debate largely breaks between “coliving” versus “micro-apartments”—that is, people who believe we’re better off building big, shared units with each tenant in a private bedroom versus those who believe we should build lots of tiny apartments each with its own little kitchen and bathroom. While each serves a similar need, they differ in some pretty important ways.

I get asked about this a lot because over the past decade I’ve had a hand in the development and management of thousands of units of each, so I’ve seen the upsides and warts of each model. Coliving has ardent supporters and arguments in its favor, but most real estate developers tend to gravitate to the more familiar micro-apartment typology.

In today’s letter I’ll share my observations and take—the good, bad, and ugly of each model, including some stories from the trenches.

What’s a unit, anyway?

Before we dive into the pros and cons, it’s worth spending a bit of time aligning on what, exactly, we’re talking about. To this point, this conversation has probably been confusing to people in the UK who call micro-apartments “coliving” and coliving “shared houses” or “HMOs”. Alas.

Fundamentally, the difference between micro-apartments (small private units) and co-living (private bedrooms in shared units) comes down to how, legally, a “unit” is defined. I know far more about this than I’d like, as coliving operators like Common had to carefully avoid creating an “SRO” (single-room occupancy), which are illegal to build in most American cities. Effectively, this meant ensuring that tenants were “living together” in a unit rather than separately in individual bedrooms. While the law doesn’t define what that means, most inspectors consider either exterior bedroom door locks or kitchen appliances in bedrooms as sufficient evidence that a developer is running an illegal SRO.

In many cases, coliving bedrooms have private bathrooms but rarely, if ever, private kitchens as this would make them legally separate units.

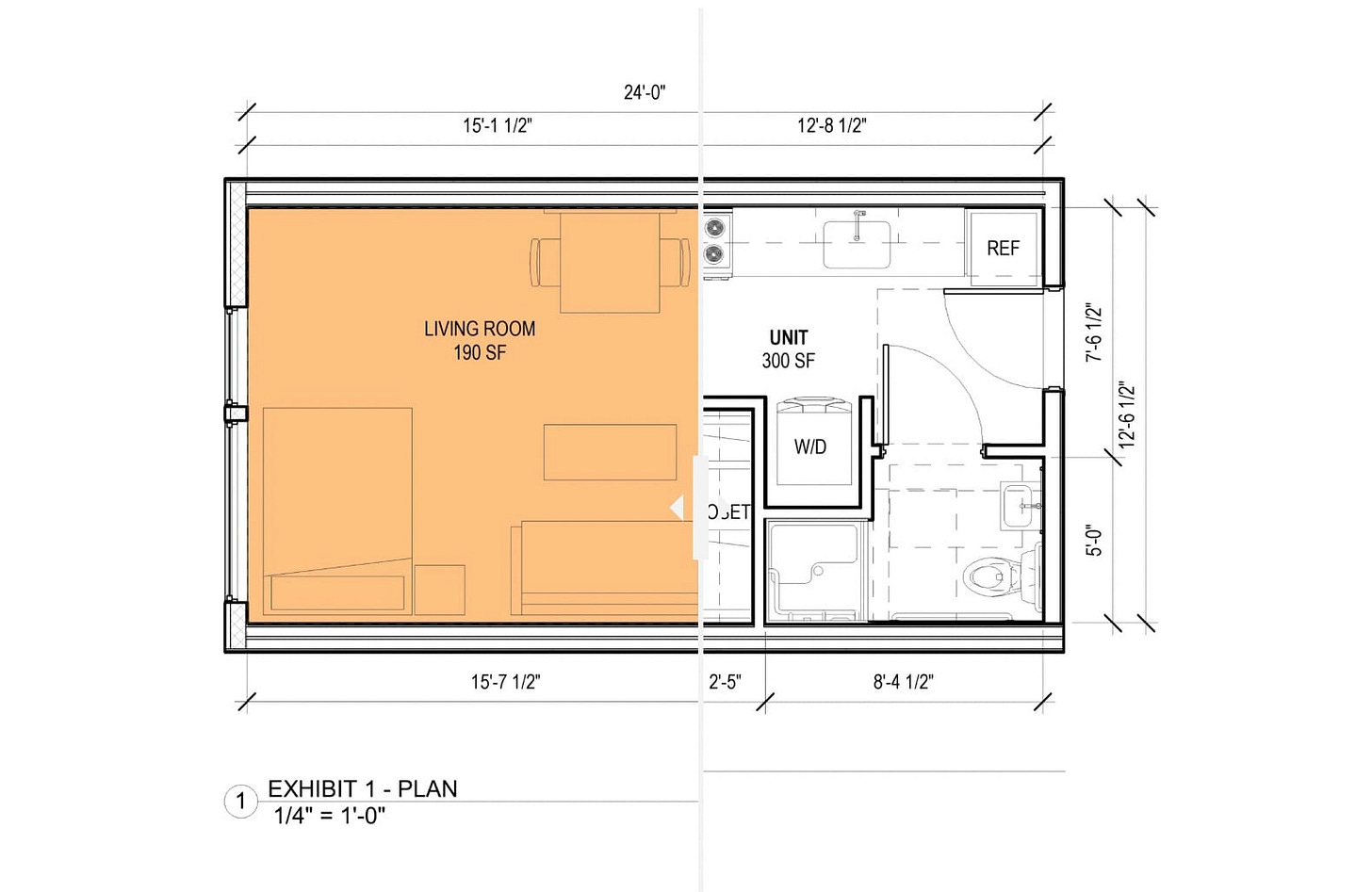

Micro-apartments avoid this dance by simply entitling each room as its own unit. Layout-wise, many micro-apartment developments look similar to hotels: small units in rows along a double-loaded corridor.

While each jurisdiction has its own rules, cities generally enforce a number of minimum standards to qualify a micro-apartment as a legal unit. Each micro-apartment almost always needs its own bathroom and kitchenette, and cities set varying minimum unit sizes—usually ranging from 250 to 400 square feet—as well as minimum dimensions.

Both co-living and micro-apartments can range in terms of quality, access to amenities, and level of programming / “intentionality” in their management. Intentional coliving communities like Radish are a different thing entirely and can be done with either wholly private units (as in many cohousing communities) or shared accommodations (Radish has a mix of both).

I. Hot Dogs and Hamburgers

To begin, I’d like to dispense with the myth that one format is objectively better than another from a user experience standpoint. People have different preferences and desires. For some reason, many in the real estate industry tend to forget that fact when it comes to housing. Few things spark more outrage than someone else’s housing preferences being different than one’s own, and many are quick to argue that those preferences should, in fact, be illegal.

We’ll get into the psychographics of the people attracted to each typology in section (IV) below. But it’s unquestionably true that some people prefer shared-unit coliving formats, and others prefer private micro-apartment formats.

The one caveat I’d make is that coliving tends to have better outcomes than micro-apartments. Our coliving units generally had higher renewal rates than our micro-apartments, and residents of coliving units were generally happier and more engaged. I’ll get a bit more into the reasons for this later on.

II. The Pro Forma

From a financial perspective, I’ve seen arguments for superior performance from both micro-apartments and coliving advocates. The truth? It depends.

Both typologies rely upon higher density to achieve superior NOI and cash-on-cash yields. How much yield can be enhanced, then, is heavily dependent on how densely each typology is built—and whether customers in a given market are willing to accept that level of density.

In most markets, units smaller than 350-400 square feet are difficult to legally build. Minimum unit dimensions, square footage requirements, and other tripwires prevent smaller units. For instance, jurisdictions such as New York have “average unit size” requirements that make the density argument for small apartments moot as those units must be counterbalanced by lower-yielding larger units.

In those markets, coliving typically wins from a pro forma standpoint. While coliving bedrooms generally rent for 15-25% less than 400 square foot studios, they don’t need to follow the same regulatory guidelines—they aren’t independent units, after all—and can be built much more densely.

But that math goes out the window in markets where micro-apartments can be built at higher densities. In Seattle and Washington DC, for instance, micro-apartments smaller than 350 square feet were legal and generated higher yields than comparable coliving plans. Seattle, for instance, recently allowed units as small as 180 square feet, though those rules have since been tightened. Yield-wise, no coliving layout can compete.

Coliving also typically wins on construction cost, coming in roughly on par per square foot with conventional multifamily. While coliving layouts generally have more bathrooms and a few additional mechanical requirements, they also have fewer kitchens, and kitchens are among the most expensive things to build. Micro-apartments, on the other hand, have more kitchens per square foot as each unit needs its own.

Of course, just because you can build it doesn’t mean local renters will want it. Seattle has a large population of tech workers and students who appreciate micro-apartment living. But not every market will tolerate that level of density, and the fallback—master leasing or selling the building to the city as affordable housing—isn’t always available.

III. The Lender’s View

For many developers experimenting with new kinds of housing, the product they choose isn’t really up to them: it’s all about the lender. Without debt, it’s next-to-impossible to get any housing development to pencil.

For a lender, a micro-apartment is weird but intelligible. It’s a small unit. Perhaps a very small unit. But it’s still an apartment, and at some price someone will probably lease it.

Coliving, on the other hand, is a freak of nature. For many commercial lenders—generally conservative, suburb-residing family people—the idea of tenants choosing to live together in a coliving environment is incomprehensible. They probably have numerous operational concerns—some valid, others based on perception.

In practice, this has been the single biggest reason why micro-apartments are more numerous than coliving: it’s far easier to get the lender on board. Micro-apartments are an incremental shift, whereas coliving is an entirely new paradigm.

IV. Renter Profile

The least appreciated difference between coliving and micro-apartments is who they attract, and there’s no easy explanation for it.

Coliving is fairly straightforward and predictable: it draws young professionals, men and women both. At Common, the median age of tenants in our coliving portfolio was around 26 years. Coliving attracted a wide range of incomes; it wasn’t rare to see people earning over $250K per year living in $1,500-per-room coliving units.

Above all, coliving was a high-trust product that attracted people of high socioeconomic status. They may not be wealthy today, but they probably grew up in an upper middle class suburban household. (We could call many of these folks ‘downwardly mobile,’ but we’ll leave that discussion for another day.)

The “working class”—people of lower socioeconomic status working “manual labor,” manufacturing, or lower-status service jobs—were wholly uninterested in coliving.

Micro-apartments, on the other hand, attracted a far broader audience. Sure, some young professionals chose the micro-apartment over coliving. But micros were also popular with the working class and a wider variety of age and demographic groups. Renting a micro-apartment didn’t require embracing a new paradigm about living; it was simply a smaller and more affordable version of something with which they were already familiar.

From an audience standpoint, micro-apartments are closer to workforce housing than they are to coliving. Whether someone chooses to rent a $1,200/mo micro-apartment or a $1,800/mo one-bedroom in a Class B- garden-style community just comes down to life stage—if they have a kid, they’re going to rent the one-bedroom and take the additional commute time on the chin.

V. Operations

The operational challenges and nuances of each typology are downstream of their respective renter profiles.

Coliving certainly presents a higher volume of issues. Upper middle class-originated young professionals are quick to complain, especially when assigned roommates they don’t already know. Often their expectations have been set by their parents’ suburban house and their last off-campus student housing experience, not Class B urban rental apartments.

However, the issues with coliving residents are typically neither severe nor hard to resolve. They tend to be a high-trust cohort, and serious issues are rare. The “worst case scenarios” often raised by prospective partners never materialized—at least for us.

Micro-apartments are the opposite. Micro-apartment residents are generally a hardier bunch and submit far fewer tickets. But the craziest and most dangerous situations we encountered came from our micro-apartment portfolio. Coliving residents almost never destroyed their unit; the same cannot be said for micro-apartment dwellers.

Collections are also much more of an issue in micro-apartments. Coliving delinquency generally mirrors that of Class A multifamily whereas micro-apartments follow a workforce housing profile. (Evictions, however, are much easier in micro-apartments than they are in coliving.)

Given all of this, it’s not surprising that owners tend to favor micro-apartment layouts. For most developers, the marginal yield and construction cost benefits of coliving don’t make up for lenders’ skepticism and the format’s operational needs.

But both formats are needed in the housing market, and both have ardent support among certain renters. It’s not correct to argue that one format is “better” for residents or should be favored from either a product or financial perspective without getting into the weeds—what can be built, at what density, for what audience.

On a different level, it’s frustrating to see the role of inconsistent regulations in shaping what gets built. The unit that gets built in Seattle is different from the unit that gets built in New York not because Seattle’s renters are different than New York’s but because Seattle has more liberal laws that allow the creation of units that would be illegal in New York in fifteen different ways.

There’s no safety argument. The fire death rate in new-construction, sprinklered apartment buildings is close to zero regardless of unit size.

Perhaps there’s a quality-of-life argument—but compared to what? Over 100,000 people sleep in homeless shelters in NYC every night. Even the smallest 180 square foot Seattle micro-apartment is far superior to a bed in a congregate shelter or a tent on the street. But is anyone in New York or San Francisco interested in what’s happening in Seattle?

As developers and advocates, the best we can do is continue telling the stories of these typologies—not hiding their warts—but making the case for their role to lenders and legislators alike.

—Brad Hargreaves

Suggested further reading:

4 Do's and 3 Dont's on coliving space architecture/design

Design matters for community. Let’s talk about some lessons learned.

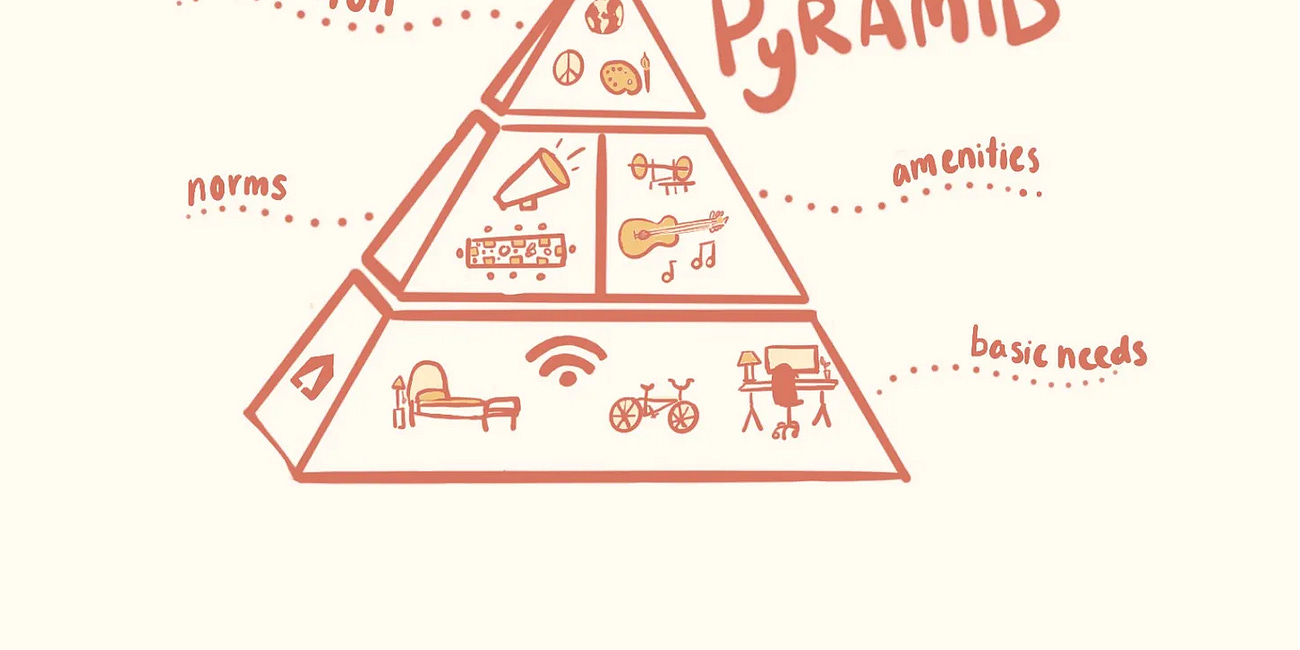

The Pyramid of Coliving Needs

This is a guest post from Jackson Steger, who leads Growth at Cabin. Cabin is building a global coliving network for creators and remote workers who want to live immersed in nature. He is also the author of Future of Living, which is about how the collision of remote work, satellite internet, the gig economy, and renewable energy enables new models of l…

Common misconceptions about coliving

‘My friends don’t understand why I’m living with a bunch of other adults. They keep asking me if it’s a reality TV show … and how much I’m getting paid.’ - Denise Umubyeyi, when moving into Casa Chironja

Interesting read, Brad. It’s refreshing to see a co-living founder with a great understanding of the site level operational challenges, of which there are many!

Have you ever considered your spaces, or other co-living spaces, as cultural infrastructure? London spaces seem to be going that way.

My thoughts on it here, keen to hear yours.

https://heidiwarwick.substack.com/p/reimagining-co-living-as-cultural