Case Study: The Dhamma Pad

A Meditation Co-Living Community in Berkeley, CA

From the editors: This is a guest post written by Georgia Perry based on an interview with Chloe Good, one of the Dhamma Pad founders. Most of the communal houses we cover don’t have a specific ‘purpose’ other than to live with friends. But the Dhamma Pad illustrates what it’s like when residents commit to a specific lifestyle - one they could do alone but knew would be better in community.

Dates operating: Feb. 2012 — Feb. 2018

Location: Berkeley, CA

Rented or owned: Rented

Amount of space: 6 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, two communal living / meditation rooms. Housed 6-9 adults; no kids or pets.

Governance: Decisions were voted on and decided by majority rule at regular house meetings. The committee model was used for handling smaller aspects.

Overview

A community house is an opportunity to create a world. We created a community and a whole world around meditation. —Chloe Good

The Dhamma Pad was a shared co-living house for people dedicated to the practice of meditation, located in the heart of Berkeley, CA.

The residents of this six-bedroom house frequently hosted community gatherings of 50-100 people in its two large communal spaces, as well as regular group meditations every Tuesday and Thursday night for 10-30 people. After a shared meditation and dharma discussion, everyone who came was treated to a delicious, healthy, lovingly-made vegetarian dinner.

In its early years, having completed at least one 10-day Vipassana meditation course taught in the tradition of S.N. Goenka was a requirement for living at the Dhamma Pad, but later the requirement was loosened so that housemates only needed to be generally interested in meditation.

How it came together

Chloe Good and her boyfriend Adrian Foley first discussed starting a meditation-focused co-living house in Berkeley with a guy they met while serving in the kitchen during a Vipassana meditation course in 2011. Adrian had lived in a house in college that provided a lot of the inspiration for what they wanted to do and inspired the name. (It was called the Dharma Pad—Dhamma is the Pāli version of this same word.)

While those initial conversations sparked ideas and excitement, things didn’t get off the ground until one year later, when the timing was suddenly right and Chloe recalls, “it just happened like magic.”

“We ran into the same guy, at the same course, in the kitchen. We ran into someone else on the street that Adrian had sat a course with and they were looking for housing. A friend of a friend knew of another meditation house closing down in Berkeley so the founder, Vlad Moskovski, joined us and brought all the furniture. We got their silverware and their dishes. We had very little money at the time, so it populated the house in a big way. It all came together in a month. The first house we saw we liked. It was sunny, it was beautiful. Not all landlords want to have a community house in their space, but the landlord gave us the lease.

“It was that dharma coming through, that purpose just flowing through you. Like when life takes you and it’s almost like there’s this invisible support that’s pushing you and guiding you and clearing the path. It’s not effortless but it felt just like the only thing to do, and it was so easy to dedicate all of our energy to it. The stars aligned in every single way, and we had a dharma house.”

Chloe believes that the organizer’s desire to serve was a reason the house flowed together so easily. “I often find this is the case,” she says. “When there’s that extra support from the universe, there’s some level of deeper meaning in it. We wanted to be an urban meditation center that was also communal and social and fun. We saw that a lot of times meditators are more isolated—it’s a solo activity. And we know that the sangha, the community, is such an important piece to developing a practice.”

Focus on meditation

The housemates at the Dhamma Pad shared one hour-long group sitting each day. It wasn’t mandatory, but as meditation was the central intention of the house, attending was a general expectation. They sat in the morning at 8am or in the evening around 6pm. It wasn’t a strict environment, but everyone was committed.

Chloe describes the vibes:

“On the weekends it was a little more fluid, but on weekdays we often would have about 75 percent of the housemates at each group sit. At one point we would ring a bell ten minutes before meditation. People would get up, and roll out of bed. Sometimes someone would be blending a smoothie in the kitchen, and we’d be meditating. Sometimes you got to meditation late, and everyone finished before you. But that was one of the core reasons we all wanted to create the house—to have an environment that pulled for us sitting one to two hours per day. There’s inspiration and support with a group doing it.”

Inner Workings

Chores

The Dhamma Pad had a detailed spreadsheet to keep track of what chores needed to be done and how much time each task took. Everyone had different roles, from mopping floors to watering plants, taking out the trash, cleaning out the fridge, and collecting and paying the rent. People would pick what chores to do based on what they liked best, but the main priority was making sure everyone was spending about the same amount of time each week—which, according to their (very) detailed spreadsheet, worked out to be 3.8 hours per person per week.

Beyond the designated weekly chores, the Dhamma Pad had a general agreement that before someone left a room they would do a once over and take their stuff out, so common areas were generally kept tidy.

From time to time, they also took part in the great co-housing tradition of shared work days or work parties. “We’d take on the kitchen one day and all just go to town on the kitchen. We all showed up for two or three hours and we were just throwing things away that are dirty, scrubbing oil off the cabinets. We did the garden another day. We built raised beds, that was a group project,” Chloe remembers.

Food & Finances

“We had very little money. We were younger, we’d all been traveling and working in different creative ways,” Chloe recalls, half-joking that the Dhamma Pad was something of a “Saturn Return house” in that a majority of people who lived there or got involved were around their late 20s, the period when Saturn returns to the same position it was at when you were born and can be a potent life development stage.

Rooms at the Dhamma Pad rented for between $700 and $1000, and all food was shared. Everyone had a personal shelf in the kitchen and there was a personal fridge for anything housemates wanted to purchase for themselves. An added fee of $150-200 was tacked onto rent monthly, and that covered everyone’s food and any necessary house goods. The amount of the fee was adjusted slightly depending on the house’s collective desires at different times, for example whether to include meat in the grocery budget or hire a monthly house cleaning service.

Housemates took turns cooking for everyone once a week, making enough for dinner along with lunch the next day (so ~12-18 meals total 1x weekly). You always had a buddy to cook with, and it was expected to take 2 hours of your weekly 3.8-hour chore time. Housemates sometimes organically came together to share mealtime, but there wasn’t a requirement or expectation to eat together. “Most of the time there were a few people. Otherwise the food would just be in the fridge for you,” Chloe says.

When cooking in bulk with leftovers like this, Chloe offers a good tip of labeling the food with the date you cooked it—a strip of masking tape and a Sharpie will do. That way, you’ll know when to clean it out. “That worked…mostly,” she says with a little laugh. (It was also someone’s designated chore to go through the fridge every week or two and clean out old food.)

The house also collectively shared the expense and effort of preparing dinner for around 10-30 meditators who came to community group sits twice weekly on Tuesday and Thursday evenings at the Dhamma Pad. On Thursdays, they held a Vipassana meditation sit for people who had completed a course in that specific tradition, and on Tuesdays they hosted a more general meditation for anyone. People who came to the meditations were welcome to come early or stay late to lend a hand with cooking or cleaning up, but they weren’t expected to—the house did it as an offering.

“We just pitched in. We made vegetarian food, and we were really good at sourcing things in bulk - lentils, rice, spices, loose tea. We would go to the farmers’ market, order in bulk from a food distributor, and eventually as time went on some people would donate food to us. We had a connection with an organization that made food for the community and we would sometimes get their leftover vegetables to make for our Tuesday and Thursday meals. But the house really did have a spirit of generosity. Everyone who came through was on board. [As housemates] we had other issues, but never was it an issue of “we can’t offer meals to the community anymore.” We did have conversations about avocados! But making lentils and salad for everybody, it probably cost around $50 a week total.”

Beyond food and everyday supplies, purchases were a mix of do-ocracy and some other strategies for collective decision-making.

“If something was under $50 and we saw it was a house need, we could buy it and get reimbursed as long as we didn’t do that all the time. We got reimbursed when rent was paid on the 28th of each month,” Chloe describes. Something above $50 would warrant a ‘hey everyone?’ message to the house group text thread or a discussion at a house meeting.

For larger purchases, such as a new Vitamix or a couch, the Dhamma Pad would save for it by accruing the money over time and collecting it in their house bank account, which was a separate account opened by one of the housemates.

Governance

“Our house was very high-touch, very involved,” recalls Chloe. She adds with a laugh, “My sister would call us ‘the Ivy League meditators.’” In addition to the meticulous spreadsheet that kept track of costs and all logistical details (ex. 3.8 hours of chores weekly rather than just 4), there was also an official key principles document outlining house values. One of them was “to be willing to communicate from the heart and grow this skill.”

There’s a continuum to consider, Chloe says, when starting a group house: how high-touch do you want your living space to be? It can sometimes be a lot of effort that not everyone may desire, but on the other hand it reaps benefits. At the Dhamma Pad, Chloe says all the collective effort led to a strong “group field.” Or, to put it another way, “People walked into the space and they could FEEL the dhamma vibes!”

The Dhamma Pad had weekly house meetings in its first years and later switched to every other week. Meetings lasted around two hours, and duties rotated for who ran the meetings and did different roles.

Throughout the week housemates freely wrote or “parked” their discussion items on a white board in the kitchen called “the bike rack.” This process gave everyone a chance to familiarize themselves with what would be talked about in the meeting beforehand. At meetings, items would be prioritized and then given an amount of time to discuss. If more time was needed it could be added.

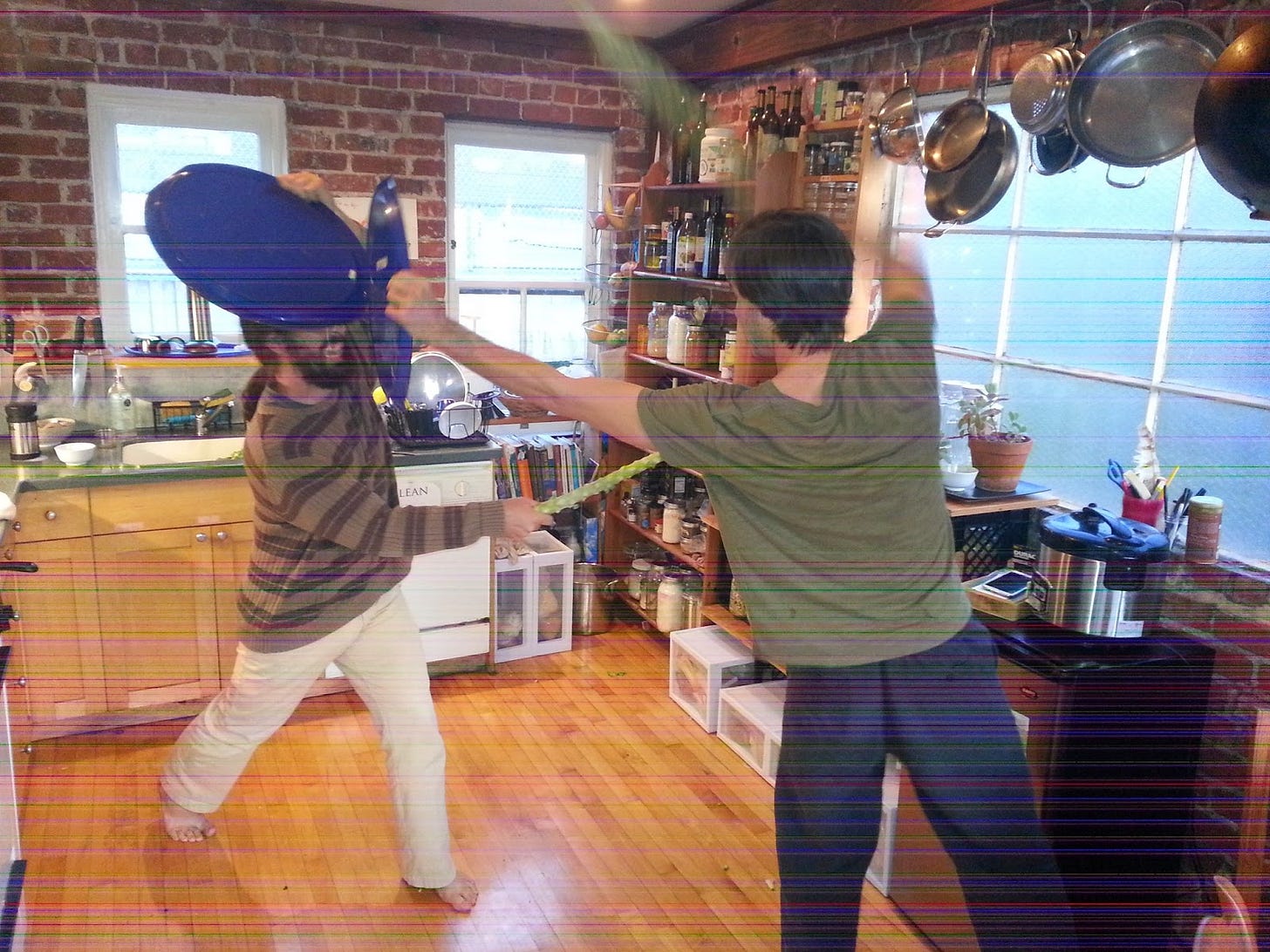

Before the meeting the house would usually cook a dinner and eat together, occasionally have a short dance party, then have a short meditation followed by a check-in of a minute or two each of how everyone’s feeling and what’s going on in their lives before jumping into the agenda items. At the end of the meeting would be announcements—anything from “We’re having this event, or this guest” to “Please remember to wash your dishes.”

For smaller house decisions and projects, the Dhamma Pad used the committee model. “We wanted to spruce up our living room. So the three people who were interested in that got together and created a plan and got certain things approved,” Chloe describes as one example.

For anything else, they had a GroupMe text thread. “This was back in the day,” Chloe laughs. “Now you would probably just have WhatsApp, but there was ALWAYS ONE person without a smartphone!”

Lessons Learned

Since the Dhamma Pad was both an intentional meditation community and home, it was important that people who lived there be a good fit on both aspects. “Do you want to meditate?” was an important question for any potential housemates.

Beyond that, a spirit of generosity and ability to get along with others well was a shared quality that made the house successful. “With our attention, time, resources, we would help each other out…Everyone came from a very service-oriented mindset and background,” Chloe says. For example, usually only a few housemates had cars at any given time, but they would let the others share them.

Meditating together goes along with the service mindset, too, Chloe says. “Because it’s an act of generosity and contribution, in a way. To show up at a certain time, to create a group field, and meditate together.”

With that framework in mind, some of the co-living lessons that grew out of the Dhamma Pad are:

Housemate selection:

The Dhamma Pad had a couple rounds for its roommate selection process, beginning with 15-30 minute phone chats to see if it was a good culture fit. The top five potential new housemates would come over for a 30 minute in person chat with all housemates—all seen in a back-to-back block of three hours. After that, they invited two or three to come over and make dinner together with everyone, and then they made the decision from there. While this process was important, Chloe notes that gut instinct was just as much so. “That intuitive hit was the best marker of whether someone was a good fit or not,” she recalls.

Shared qualities are important. For the Dhamma Pad, agreeableness and extroversion were two primary qualities they landed on. “My theory is that it’s easier for people who are more agreeable to live in community,” Chloe says. “It’s easier for them if someone moves something of theirs, or if someone eats the last head of kale! Or the last avocado. Because that’s gonna happen.” Extroversion was beneficial because they held so many events. If someone would just prefer to be in their room the whole time, that wouldn’t really be a good fit at the Dhamma Pad.

Keeping an open mind to housemates who have a general interest in whatever the house is about can work just as well or better than being sticklers for housemates who have extensive experience or skills. For example, at first the Dhamma Pad had a policy that all housemates had to have completed a specific Vipassana meditation course in the tradition of S.N. Goenka, which is how they all came together initially. But after a short-term subletter who was interested in meditation but hadn’t sat a course turned out to be an absolutely wonderful fit, they loosened the rules around that.

Hosting guests:

It’s not nothing to host guests—especially if it’s happening a lot. Getting clear around how people like to host, and their guest hosting style, was an important learning curve at the Dhamma Pad (editor’s note - we think this is one of the top three things you need to agree on as a community!). In the beginning, the house was quite loose with its guest policy but that evolved over time.

“It was very open, which was fun. We made some really cool friends. Friends would send people from the Vipassana Center over to our house. We’d get a lot of ‘dharma travelers’,” she remembers with a smile.

“It was a really sweet thing, but at one point we became like a boarding house, and we had to [alter our policy]. We were busy and we were like, ok, only people that you really love and want to spend time with.”

They also began asking guests who stayed more than three days to make a contribution to the house, so things felt more in alignment. Guests could either pay $15 a day plus $15 a day for food (so $30 total) or pay $15 a day for food and do an hour of contribution a day. “We actually got a lot of cool projects done from guests. Or they would cook for us sometimes,” Chloe says.

Conflict resolution:

“Living in community is a very fast personal growth path. Relational growth and just being faced with the things that trigger us,” Chloe says. “We came together as a meditation house and then we all realized we needed more skills to fully navigate conflict. It inspired a lot of us to get more skills and to study communication and to go to trauma healing therapy and to work out our deeper psychological work.”

Some of the tools they found helpful:

Learning how to use nonviolent communication and “I”-statements. [https://www.bumc.bu.edu/facdev-medicine/files/2011/08/I-messages-handout.pdf] “I find taking responsibility for our own experience is really important in community because someone else could be in the same experience and not react the same way,” Chloe says.

Trying out T-groups. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T-groups] “‘I noticed I’m feeling less connected to you.’ You might say something like that. They might say, ‘I feel sad hearing that. I also feel less connected to you.’ Just get things out in the open. But doing it in a way that’s not blaming or shaming the other person,” Chloe explains.

Going on camping trips together. “It was really effective to do little trips or retreats together. We’d do bonding activities, sometimes t-group, we might do a visioning exercise of the house,” Chloe says.

Doing a day-long meditation retreat in the house.

They worked on these conflict resolution and communication skills throughout the whole six years the Dhamma Pad was in existence. Chloe says she realized she had more work to do than she thought, once the house got going. This can be a common experience with shared living.

Likely because of this kind of growth work, along with the other aspects shared in this article, Chloe reports that, at the end, the house remained “on good terms with everyone.” Despite having several roommates in and out over the years, including some people who moved out due to things not working out, a lot of past housemates would come to events and gatherings, and stay connected.

In Conclusion

From Chloe: “The Dhamma Pad grew from a deep desire to build community around Vipassana meditation. Over time, our focus naturally shifted toward new paths — starting businesses, moving abroad, getting married, having children — and the space no longer matched our evolving needs. Many of us also felt called to live closer to nature, away from the city center.

Yet the spirit of the Dhamma Pad lives on. Many of us still gather regularly and maintain dedicated, consistent meditation practices.

It’s with nostalgia, a touch of sadness, and even more joy that we share the story of the Dhamma Pad. It was an era that touched the hearts and souls of so many — a spirit of generosity, love, community, fun, and transformation that continues to live inside all who stepped into our home.”

Chloe Good is an Attachment Repair Somatic Executive Coach and helps executives and leaders find deeper meaning and greater impact in their work by healing their early attachment trauma. She was a Leadership Professor at Stanford & Sonoma State Universities for 8 years and consults Leaders at companies like eBay, Accenture, Square, Facebook and various San Francisco Bay Area startups aligning leaders to their higher purpose to create the world we all want to live in. Learn more or see what it’s like to work with Chloe at www.chloegood.com.

Georgia Perry is a freelance writer and journalist who has reported extensively on housing across the U.S.---from tiny home villages and homeless encampments in Oregon to multi-million dollar vacation rentals in Vail, Colorado. From 2014-2015, while living in Oakland, California, she regularly attended events at the Dhamma Pad. To find more of her writing, check out her free e-zine Banana Phone Crisis Line, which she publishes thoughtfully and not terribly often.

Curious about living near friends or coliving? Find more case studies, how tos, and reflections at Supernuclear: a guide to coliving. Sign up to be notified as future articles are published here:

You can find the directory of the articles we’ve written and plan to write here.

Well-written and edited! A good balance between touch-feely aspects and technical-financial aspects.