Fairness is overrated and bragging is underrated

Motivational systems for coliving (and beyond…)

This particular lesson has shifted my worldview significantly.

It’s something I’ve learned in coliving environments, but I believe it applies to most groups.

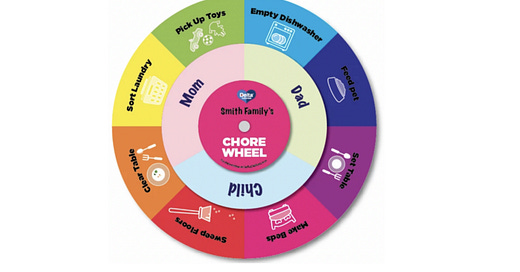

Consider the chore wheel

It’s pretty straightforward how the chore wheel came about.

There are things that need to get done in a community.

There is a group of residents to do those things

The solution seems obvious: Split the tasks up roughly evenly between people in the group and memorialize all of this on a wheel.

The critique of the Chore Wheel

Problem #1: Perfection is merely adequate, imperfection is disappointment.

What’s the best case scenario with a chore wheel? Everyone does their thing.

What’s your reaction when this happens?

Week 1: “Great, it’s working”

Week 2: “Oh good, still working”

Week 3: *Shrug*

This is the best case long-term scenario of a Chore Wheel. An accustomed shrug.

But anyone who has had a chore wheel for more than a few weeks knows what actually happens.

It’s week 4 and stupid Richard didn’t take out the trash. It was his turn to take out the trash on the chore wheel. And hey … why am I unloading the dishwasher if Richard didn’t take out the trash? I’m not going to do it tonight. Take that, Richard.

All Chore Wheels eventually lead to one place: Disappointment with your fellow (wo)man.

People are imperfect and anything less than perfection (with a Chore Wheel) is a let down.

Problem #2: Upper limiting

Chore Wheels are finite.

There are a fixed number of things on a chore wheel. Let’s say 6.

Everything on a chore wheel might be a good thing. But only 6 good things can happen.

Chore Wheels are upper limiting. In a perfect world, 6 good things happen, but never 7. And certainly never 25.

Once I unload the dishwasher I’ve “done my part.” My motivation to do other things has evaporated. The whole mental model is “just do this one thing.”

Problem #3: Gratitude schmatitude.

Suppose a friend came to your house and took out your trash when you weren’t looking. How would you feel? Probably pretty damn grateful.

Now suppose someone took out the trash because the Chore Wheel told them too. Do you feel grateful?

No, I don’t feel grateful. That mofo owes me because I emptied the dishwasher.

Suddenly, we forget that there’s a group of people making our lives easier. Action doesn’t deserve gratitude. It’s merely what was supposed to happen. The cheer wheel conceives of contribution as repaying a debt, not an act of generosity. It’s about policing lack of action, not inspiring more action.

== The metaphysics of the Chore Wheel: Fairness ==

Fairness.

When you dig deep enough that’s what the Chore Wheel is about.

Your frustration at Richard boils down to “it’s not fair!” Your lack of desire to do additional tasks not on the chore wheel is again “it’s not fair!”

The Chore Wheel is the physical manifestation of our desire for fairness.

I want to make the case against fairness.

Fairness is a scarcity mindset.

The scarce thing that a chore wheel tries to allocate is people’s level of contribution. It conceives of contribution as a non-renewable resource in a contribution economy. Creating more desire to contribute is impossible or costly.

In a world where your capacity and desire to contribute was abundant, rather than scarce, you wouldn’t be concerned with whether Richard was supposed to take out the trash. You’d just take out the trash.

== Sidebar: Wikipedia is unfair ==

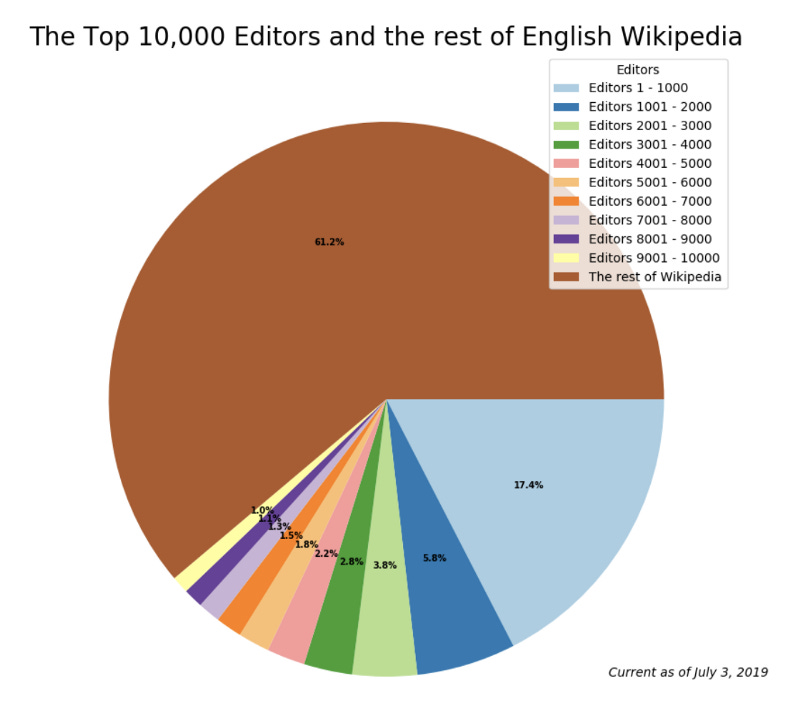

77% of the content on Wikipedia is written by 1% of its editors and a fraction of 1% of its users.

10k people write most of Wikipedia

Totally, utterly, insanely unfair. If Wikipedia was a country, the Pareto efficient (a measure of inequality) would be worse than South Africa during Apartheid.

Imagine if Jimmy Wales in 2001 instead decided to start “Fair Wikipedia:” He’d employ something that looked more like a Chore Wheel.

Does anyone think Fair Wikipedia would get off the ground?

What motivates the 1% of power authors on Wikipedia? It can’t be fairness. Wikipedia is utterly unfair.

They likely couch things in abundance. Something like “this gives me meaning” or “this is my contribution to the world” or “I wanted to give back to the others writing articles”

My guess is that Wikipedia authors, if you ask them, have a deep-seated feeling of Abundance. That they are grateful for something, and churning out endless articles without compensation is their way of adding to the abundance.

(The same is probably the case with authors of open source software)

The alternative to Chore Wheels: The “Brag Sheet”

I credit my understanding of this to two extraordinary women.

Zarinah modeled how this worked in reality at The Embassy. Kristen helped me understand the behavioral science behind it.

At RGB, we have a Slack channel called “BilboBraggins” (name borrowed from Embassy SF).

At the Radish, we call it “I_did_a_thing”

Both of these are forms of Brag Sheets.

^BilboBraggins: A Slack Brag Sheet

There are no chore wheels in these coliving communities. The Brag Sheet takes the place of a chore wheel.

How does it work? When you see something that could be done to make the community better, you just do it. Then you post that you did it.

You brag.

Not humble bragging. (“I feel so fortunate to live in an environment where I am able to take out the trash”).

Not generic bragging (“I take out the trash a fair bit”).

Real earnest, specific boasting. (“I took out the trash for you all tonight”)

But wait … isn’t bragging bad? Shouldn’t we all just do good things and not make a big deal about it?

Bragging is the fuel that sets the Brag Sheet flywheel spinning:

1. It allows people to see all of the abundance that it being done for them

2. It allows people to get credit and recognition for doing things.

3. It ingrains a social norm that people contribute without being asked.

The mindset changes: “Look at all of these things people are voluntarily doing for me. Look how fortunate I am. I am so grateful.”

… and then soon …

Let me express my gratitude by giving back.

And back to Wikipedia or open source software for a bit. They actually make “bragging” fairly easy. They just do the bragging on behalf of people.

But really, how does everything get done?

I swear to you, we get done most chores most of the time without any “chore” system.

People actually look for ways to contribute and then they brag about it. They don’t need to be told.

Even “bad” tasks like taking out the trash get done. There’s someone at RGB who took out the trash every week as his act of service. There’s a woman at Radish who empties the pee tank in the guest RV as her act of service. And if they don’t do it, someone fills in to pay it back. You never get a “that’s not my job” attitude like you would with a chore wheel.

Stop problematizing unequal contribution!

What if we all decided it wasn’t a problem that some people do more than others?

Problematizing unequal contribution is a surefire way to generate bitterness. “Equal” is hard to achieve and unstable. People’s lives ebb and flow, and so does their time, desire, and ability to contribute. My coliving wisdom for you: Capture the upswings and don’t begrudge the downswings.

This is not to say that we should let people off the hook who don’t contribute at all. Everyone should be contributing. Contribution is a core value at every coliving community I’ve been a part of. And we have serious conversations with people who consistently fail to contribute. It’s just that you don’t need to equalize contribution.

And if you start a coliving community, expect to do a whole lot more than everyone else. Your choice is whether to see this as a source of bitterness or a warm source of pride.

Systematizing it

Features of a chore wheel (boo!);

A list of chores: A pre-defined, finite list of things that count as chores

Assignment of individuals to those chores

An accountability system to surface when someone didn’t do what they are supposed to

Features of a Brag Sheet (yay!):

Wish list: A running list of things people would like to see get done

A social norm of bragging: A place to share ways in which you contributed to the group.

A defined group of people: This relies on social ties, social capital. The group needs to have boundaries.

Letting go of fairness: Not problematizing unequal contribution.

Beyond Coliving?

I believe this goes well beyond coliving. KPIs are the work version of a chore wheel. Fixed taxes are the civic responsibility version of a chore wheel.

Think through every group you are involved with. Does the underlying motivational and contribution architecture look more like a Chore Wheel or a Brag Sheet? If the former, maybe play around with seeing how you could make it look like the latter.

—

I don’t think this would work on the scale of nations. But homes build up to streets, streets build up to neighborhoods, neighborhoods build up to cities, cities build up to states, and states build up to nations. Perhaps the Brag Sheet is motivational architecture for a better world.

Curious about coliving? Find more case studies, how tos, and reflections at Supernuclear: a guide to coliving. Sign up to be notified as future articles are published here:

You can find the directory of the articles we’ve written and plan to write here.

Hit us up?

hi@gosupernuclear.com

Thanks for this article. I came here by accident (serendipity) via the article on the “ The 9 types of people you find in coliving” and absolutely love it. My “coliving situation” is that as a family, so there might be some differences.

Right now, we employ a chore wheel for the kids/teens to get them going - as we, the parents, obviously have a number of other chores we can’t or right now didn’t want to put on the table to not overwhelm them (but which we “brag” about whenever the kids complain about their chores).

Looking at it from the perspective of “Chore Wheel” vs. “Brag Wheel”, I see we’ve probably missed an opportunity and have done it all wrong.

Naturally, when the kids were younger they loved to contribute. Since there never was any bragging involved in the later stage where we wanted to more systematically involve them in the family chores and the things done that contribute to our family and it’s wellbeing and “well-running”, we probably missed that/an opportunity then to turn this voluntary contribution into something more systematic for the benefit of the whole family.

So, maybe it’s time to shift from chore wheel to brag wheel. I was just wondering whether anybody reading this has some experience with brag wheels in families, particularly with respect to its members and their “time, desire, and ability to contribute”?

So good. Thank you for explaining something I’ve felt for a while, but couldn’t yet articulate.

I lived in a co-living house for about eight years and observed both the scarcity mindset and resentment in me that would come with fixed chores and the beautiful generosity that would arise in me when I was just doing what I could see was needed.

I now live with my partner in a budding apartment building that we hope to transform into something akin to Fractal in NYC. When my partner and I started living together, we oriented towards cleaning from a place of capacity, desire, and generosity.

Capacity means if we both are zonked we don’t clean and that’s completely OK. It also means that if we’re very focused on other things that are more important to us like work or projects and that’s where our capacity is focused then our house can get a little crazy… And that’s OK. We clean from a place of capacity, not obligation and that helps to prevent resentment.

Desire acknowledges that we have different needs for our house. I feel more clear and centered in an orderly home. Whereas my partner Jon needs order less to feel good. So I clean in such a way that helps me feel clear because I want that end result. Jon isn’t very messy so this doesn’t bother me.

Generosity i.e. love means: because we love each other we don’t want undue burden to fall on the other’s shoulders. We always want to make our home better and more enjoyable for our sake and our partners sake, so if we have the capacity we give ourselves to the little moments of cleaning and the big projects.

I’ll also add that we both hold a longer time horizon when it comes to contributions – sometimes one of us will feel guilty that the other is doing a lot to take care of us that day. But the one doing more can see that the game of being together is long. Making sure that both people contributed equally at the end of each day as a recipe for resentment where as trusting the other to show up and generously showing up yourself, is a recipe for continued abundance and a whole lot of love.

Most of the time our house is pretty orderly. Sometimes it’s a hellhole. We’re enjoying the ride and we spend most of our time doing things that really matter to us.